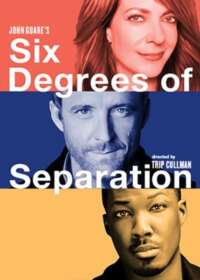

He’s embarrassed, but his father won’t be checking into “the Sherry” down the street till the next morning. Paul (Hawkins) was mugged, he says, and found himself outside the Fifth Avenue apartment home of his Harvard chums, Flan and Ouisa’s kids. Suddenly the doorman appears, holding up a preppily dressed young black man, disheveled and bleeding from a stomach wound. The couple is scrabbling around in the aftermath of what appears to have been a burglary, when they turn to the audience and begin telling the story of what happened the night before: At opening, the revolving work has stopped with the threatening side facing us. Flan (Hickey) and Ouisa (Janney) turn it around according to their mood. The living room is dominated by a rare Kandinsky work painted on both sides of the canvas, dark and abstract on one side, bright and abstract on the other. We’re in the artily appointed Upper East Side home of Flanders and Louisa Kittredge, Flan and Ouisa for short. Guare, however, using a brief, intriguing newspaper report as his jumping off point, found a way in Six Degrees to make us laugh in the face of our own insufficiency in bridging that midnight-dark gulf. That’s a theme for the ages, from Moliere to Arthur Miller to Tony Kushner. Or, more likely, Six Degrees transcends its particulars and addresses something ineffably human: The terrifying gulf between how we see ourselves and how we need others to see us. On the evidence of the spectacular revival that opened tonight at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, with a cast led by Allison Janney ( Mom, The West Wing), Corey Hawkins ( Straight Outta Compton) and John Benjamin Hickey ( The Normal Heart), either it’s been a very long moment that Guare captured. When Six Degrees of Separationopened off-Broadway, and then on, late in 1990, we thought the genius of John Guare’s excoriating comedy lay in the perfect way it captured a moment in a particular subset of American culture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)